The Taurian Journey

Compte Louis Philipp de Ségur, French ambassador to the Russian court in St. Petersburg, discovers the beauty of the Dnieper in Smolensk in the winter of 1786/87:

La position de cette ville est très pittoresque : la beauté du Dniepr, la rapidité de ses eaux, qui annoçent presque dès sa source la majesté qu’il déploie à Kioff, et qui s’accroît jusqu’à sa chute dans le Pont-Euxin, l’escarpement de son rivage, les bâtiments en amphithéâtre qui le décorent, les ravins inégaux que la nature a placés dans les flancs de cette montagne, les maisons, les jardins, les vergers dont ils sont ornés, offrent le point de vue le plus singulier au voyageur qui, franchissant les voȗtes hardies de ses ponts, aperçoit au-dessous de lui, au fond d’un abîme, cette ville artistiquement dessinée. (3, S. 30). La position de cette ville est trés pittoresque: la beauté du Dniéper, la rapidité de ses eaux, qui annoncent presque dés sa source la majesté qu’il déploie à Kioff, et qui s’accroit jusqu’à sa chute dans le Pont-Euxin, l’escarpement de son rivage, les batiments en amphithéatre qui le décorent, les ravins inégaux que la nature a placés dans les flancs de cette montagne, les maisons, les jardins, les vergers dont ils sont ornés, offrent le point de vue le plus singulier au voyageur qui, franchissant les votites hardies de ses ponts , apercoit au-dessous de lui, au fond d’un abime, cette ville artistement dessinée. (III, S. 30)

“The position of this town is very picturesque: the beauty of the Dniéper, the speed of its waters, which, almost from its source, announce the majesty which it deploys at Kioff, and which continues to develop as far as to the chute into Pont-Euxin, the escarpment of its banks, the amphitheatric buildings which adorn it, the irregular ravines which nature has placed on the flanks of this mountain, the houses, gardens and orchards which decorate them, offer the most singular vantage point to the traveller who, crossing the sturdy arches of its bridges, sees below him, at the bottom of an abyss, this artistically designed city.”

sin. (III, S. 30)

As Catherine II.s diplomatic companion on her legendary Taurian voyage, the Dnieper cruise from Kiev to the Crimean peninsula in 1787, which was supposedly intended to secure Russian claims to ownership of the Black Sea but was in fact preparing for the next Russo-Turkish war, he kept a diary that was published in 1826 under the title Ségur, Louis-Philippe de: Mémoires ou souvenirs et anecdotes (3) and is still of interest today because the notes not only reflect Catherine’s policy of conquest, but also – from the perspective of an active ambassador – refer to the world-changing upheaval that had set in motion in France and led to the replacement of aristocratic rule by the bourgeoisie in Europe.

The Tsarina’s entourage, consisting of the inner court, 14 carriages, 121 sleighs, 40 side-cars and 560 horses, changed at each station, had set out on 18 January 1787 and reached the winter quarters of Kiev (which Ségur calls Kioff), on 9 February. Here it was to be waited until the Dnieper would be free of ice; presumably not before May, so that Catherine had ample time to publicly celebrate her Russian Orthodox faith by frequent attendance at church services, and to display power by means of a brilliant and costly court.

Kiev was the centre of Rus and a centre of Orthodox Christianity. The Roman Catholic Ségur notices that there are no chairs or benches in the city’s churches. Prayers and singing are done standing and walking, which fills the place of worship with constant commotion.

The Christianisation legend, according to which in the 9th century a ruling prince Vladimir from a Viking dynasty that had gained a foothold on the Dnieper turned to the Byzantine rite, establishes the connection between the river myth and Christianity that becomes characteristic of Kiever Rus and is by no means absorbed in Tsarist Russia’s claim to the political succession of the Byzantine Empire. In order to put a visible end to the practised worship of the pagan gods at the time, Vladimir had the wooden statue of the idol Perún thrown into the Dnjeper. Ségur retells the legend:

Les environs de Kioff sont parsemés de plusieurs ermitages et monastères, dont les situations sont agréables et varides; on y distingue entr’autres le monastère de Vouidoubets, dont le nom rappelle une antique tradition. Le prince Wladimir, disent les vieilles chroniques, ayant reçu le baptême, résolut de détruire les temples païens et les idoles ; il ordonna donc de traîner l’idole principale, qui se nommait Peroun, jusqu’au bord du Dniepr, et de la jeter dans ce fleuve. Le peuple, attaché par son ancienne superstition au culte de cette idole, éclatant en sanglots et suivant en foule sur la rive l’idole, que le courant emportait, lui criait : Peroun, Peroun, vouidoubey, c’est-a-dire : Peroun, Peroun, sors de l’eau. Or, par l’effet du hasard, l’idole s’arrêta près du rivage, a l’endroit où l’on bâtit le monastère dont nous parlons ; ce qui depuis rendit toujours ce lieu sacré pour le peuple crédule : les moines favorisèrent cette superstition en donnant le nom de Vouidoubets a l’église et aux couvents fondés sur la plage ou l’idole Péroun s’était arrêtée (3 S.51).

“The area around Kioff is dotted with several hermitages and monasteries, in pleasant and varied situations, among others, the Vouidoubets monastery, whose name recalls an ancient tradition. Prince Wladimir, say the old chronicles, having been baptized, resolved to destroy all pagan temples and idols; he therefore ordered to drag the main idol, named Peroun, to the banks of the Dnjeper, and to throw it into the river. The people, attached by their ancient superstition to the worship of this idol, burst into tears and following the idol, that the current was carrying away, were shouting: „Peroun, Peroun vouidoubey, i.e.: Peroun, Peroun get out of the water“. And so, by chance, the idol came to rest near the shore, at the place where the monastery we’re talking about was built, which since then was sacred to the credulous populace: the monks encouraged this superstition by giving the name of Vouidoubets to the church and the convents founded on the beach where the Peroun idol had stopped.”(S.51/52)

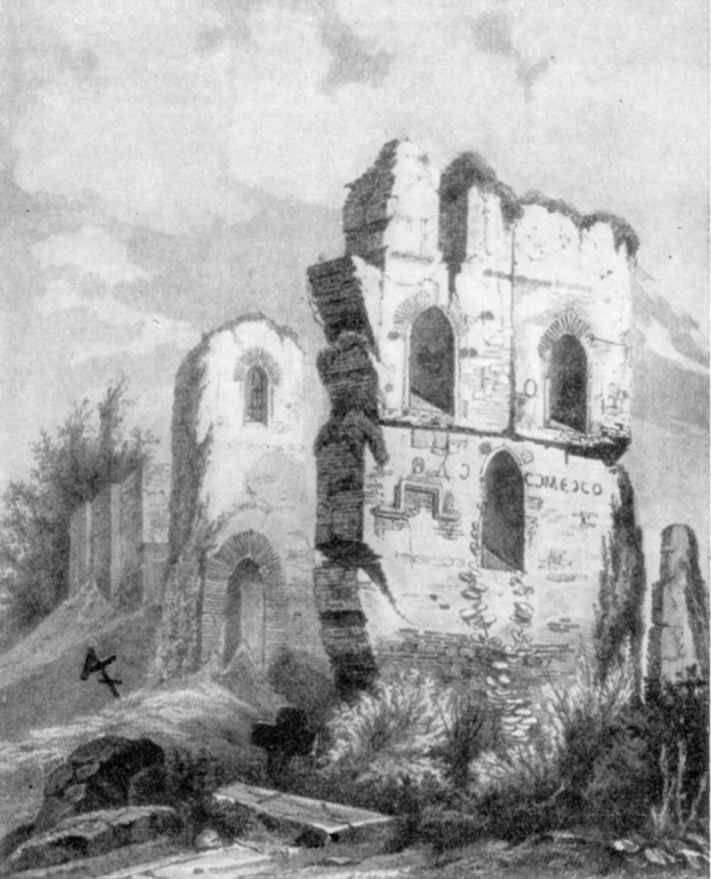

A chronicle cited by Ségur describes eleventh-century Kiev as a thriving metropolis with at least three hundred churches, three annual markets and countless inhabitants. This was before the invasion of the Golden Horde under Batu, Genghis Khan’s grandson, around 1240. The city burned down completely, presumably as a prelude to the reign of terror of the Mongol “Golden Horde”, which greatly decimated its population until its withdrawal from Europe. In Ségur’s time, Kiev’s past glory could only be read from its ruins:

Elle occupait encore, lorsque je la vis, un vaste terrain, mais qui n’offrait à nos regards qu’un bizarre mélange de ruines majestueuses, de misérables baraques, de quelques vastes couvents, de plusieurs églises à clochers dorés, et de nombreux palais ou bâtiments en pierre commencés, mais dont la plupart étaient loin d’être achevés.

“When I saw the town, she was still occupying a vast expanse of land, but all we could see of it was a bizarre mixture of majestic ruins, miserable shacks a few vast convents, several churches with golden steeples, and numerous palaces or stone buildings most of which were far from finished.”

A khanate of the Mongols, called “Tatars” by the Russians, remained in the Crimea under the protection of the Ottoman Empire and harassed southern Russia with raids from the peninsula. It was only after the Sixth Russo-Turkish War (1768 to 1774) that the balance of power changed: The Crimean Khanate freed itself from its dependence on the Turkish Sultan, which played into the Russians’ hands. After winning the war against Turkey, they were able to act as an occupying power in Crimea and began large-scale resettlements. The Tatar Crimea was Russified, southern Russia Christianised by the settlement of Greeks and Armenians. In 1783, Catherine annexed the Crimea. It has been Russian ever since. Tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars emigrated. The Taurian Journey was far more than a border inspection by the St Petersburg court, as it was officially declared. It was a move in Russia’s centuries-long struggle against Turkey to secure Russia’s access to the Black Sea.

Potemkin, Catherine II.’s general, had successfully colonised southern Russia on the Tsarina’s behalf. This was not only about “flourishing landscapes”, but also about war ports. At the European courts, people feared that Catherine intended to provoke the Ottoman Empire into another war and had her diplomats accompany the action. The Empress embarked on her galley off Kiev on 1 May 1787. Her fleet consisted of twenty-four ships with a crew of three thousand. The guests of honour were distributed among seven elaborately painted, sumptuously furnished galleys. The second of these ships was at the disposal of Prince Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin, Catherine’s long-time favourite, minister and general, to whom the French envoy Louis Philippe de Ségur paid particular attention on this voyage, for he was the only person who knew what Catherine was up to. As a lover she had replaced him with a younger officer, but as an advisor and organiser Potemkin remained the first man in the state. Ségur describes him as an often grossly rude eccentric (which may also have been a kind of protest against the slighting he received from his ever-present successor).

Resettled in the Russian parts of the country were mainly the Christian Zaporozhian Cossacks, whom Ségur sees manoeuvring in the vastness of the Dnieper valley (3, p.112). The phrase about the “Potemkin villages” does not seem to be mere malice. The Fama later insinuated that the prince had the façades of poor settlements along the route of the journey spruced up to pretend to the tsarina that they were “flourishing landscapes”. In fact, Ségur observes a carefully staged “adventure trip”:

Toutes les stations étaient mesurées pour éviter la plus légère lassitude ; il avait soin de ne faire arrêter la flotte qu’en face des bourgs ou villes situées dans des positions pittoresques. D’immenses troupeaux animaient les prairies ; des groupes de paysans vivifiaient les plages ; une foule innombrable de bâteaux portant des jeunes garçons et des jeunes filles, qui chantaient des airs rustiques de leur pays, nous environnaient sans cesse ; rien n’était oublié.

All of the stations were measured to avoid the slightest fatigue; he was careful to stop the fleet only in front of towns or cities or towns in picturesque positions. Immense herds of cattle enlivened the meadows; groups of peasants livened up the beaches; an innumerable crowd of boats carrying young boys and girls, singing the rustic tunes of their homeland; nothing was forgotten.

Souvent, on voyait des corps légers de Cosaques manœuvrer dans les plaines que baigne le Dniepr. Les villes, les villages, les maisons de campagne, et quelquefois de rustiques cabanes, étaient tellement ornés et déguisés par des arcs de triomphe, par des guirlandes de fleurs, par d’élégantes décorations d’architecture, que leur aspect complétait l’illusion au point de les transformer à nos yeux en cités superbes, en palais soudainement construits, en jardins magiquement créés.

“Often we saw light bodies of Cosaques maneuvrer in the plains that are bathed by the Dniéper. The towns, the villages, the country-houses, and sometimes rustic-cabanes, were so adorned and disguised by triumphal arches, by garlands of flowers, by elegant architectural decorations, that their aspect completed the illusion to the point of transforming them for our eyes into cities superbes, in palaces suddenly built, in magically created gardens.”

The marshy area at the lower reaches of the Dnieper, which merged with the steppes to the east, had long been a no-man’s land, a refuge for dropouts of all origins (runaway serfs, deserted soldiers) who organised themselves into the equestrian communities of the Cossacks and fought the Tartars. Since they freely chose their leaders, they are considered pioneers of modern social forms, although their Christian faith did not prevent them from robbing and murdering most cruelly. Belonging to Orthodox Christianity was obligatory for joining the ranks of the Cossacks. This protected the Rus from Islam. For a time they formed a separate class with independent jurisdiction and authority, led a semi-legal, predatory existence, but also played an important role in defending the Russian south-western border against the raids of the Crimean Tatars, for which they received food and money. Economically, they remained dependent on the state without being obligated to serve it. The hetmanate represented a shadow state with its own rules and could not produce a social revolution for lack of political self-definition. Loyalty meant obedience to orders.

The Cossacks of the southern Russian steppes were fast horsemen, the “Zaporozhians” of the islands in the Dnieper delta experienced skippers, whom Potemkin used to steer Catherine’s fleet to the Black Sea without causing damage. The ships managed the watery middle part of the Dnieper without difficulty. The distance between Kiev and Kaydak is estimated by the reporter Ségur at four hundred and forty-six Russian versts, a little under 500 km, then the ship’s company had to change to carriages for the rest of the way to Kherson. The sandbanks and rapids began at Kaydak:

Son lit, depuis Kaydak, est embarrassé par treize cataractes qui occupent un espace de soixante verstes. Plusieurs de ces rochers sont couverts d’eau, d’autres s’élèvent à une assez grande hauteur au-dessus de sa surface. Ce fleuve est rapide ; plusieurs bancs de sable y rendent quelquefois la navigation assez dangereuse (3/S.121).

“Its bed since Kaydak is embarrassed by treize cataractes, which occupy a space of sixty-yerstes. Many of these rocks are covered with water; others rise quite high above its surface. This-river-is-rapid; many banks of sand make the navigation very hazardous.”

Nos embarcations ont fort heureusement franchi ce pas périlleux avec la rapidité d’une flèche, mais également avec des mouvements violents qui nous faisaient croire qu’elles étaient sur le point d’être brisées ou remplies par les vagues et submergées ; le canoë en particulier disparaissait presque à chaque instant.

“The boats, heading our way very fortunately crossed this perilous step with the speed of an arrow, but also with violent movements that made us believe that they were about to be broken or filled by the waves and submerged; the canoe in particular disappeared at almost every moment.”

The secret meeting between Joseph II and Catherine was to take place in Kherson. The Emperor, travelling incognito as Count Falkenstein, had already arrived in Kherson the day before. It had been arranged that he would visit Catherine in Kaydak on her galley. However, the fleet had got stuck in the rapids. Catherine, informed by Potemkin, boarded a carriage and drove to meet the emperor. They met near a lonely Cossack house, talked there for a few hours and drove back to Kaydak, where the diplomats rejoined them. The fellow travellers were apparently not informed about the content of the conversation between the Tsarina and the Emperor.

The consequences will become clear later. Catherine’s plan to impose the next war on Turkey in alliance with Austria will come to fruition. Building a bridge to the future is an urban planning project. By founding the city of Ekaterinoslaff (Dnepro) at the intersection of the Dnieper valley and the steppe, the tsarina creates a common centre for the regions of Rus and southern Russia. On 20 May, tents were pitched two miles away from where the foundation stone was to be laid. And again, the landscape played a role in a historically significant decision. It is a vantage point on the river that is chosen as the centre of a new settlement.

On entendit la messe dans la tente impériale, et leurs majestés posèrent, en présence de l’archevêque, la première pierre de l’église de cette nouvelle capitale, dont la position est extrêmement riante. Elle est placée sur une hauteur d’où l’on aperçoit les longues sinuosités du BORYSTHENES, et les iles boisées qui embellissent cette partie de son cours“(3 S. 138).

“A mass was held in the imperial tent. In the presence of the archbishop, the first stone was then laid for the church of this new centre, whose location is extremely charming. It stands on a hill from which one can see the long lines of the Borysthenes and the wooded islands in the river”.